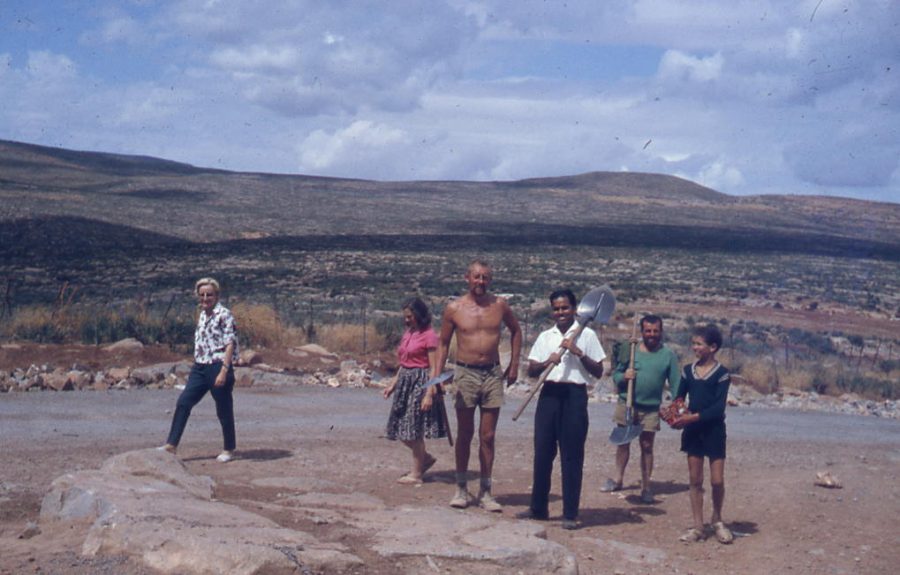

Fritz Lampert in Algeria

Name of the testimonial: Fritz Lampert

Sending Organization: S.C.I. Germany

Year of the workcamps: 1962

Place of the workcamps: Tell-Atlas mountains in Western Algeria

What was your motivation to join a workcamp?

Since 1830 France had occupied Algeria and had made it the granary and essential part of La France d’Outre Mer versus Al Jaza’ir , an independent Algeria, with a population of over 11 million Arabic-speaking moslems, mostly Berber tribes. Algérie Français represented the million-strong French settlers.

The Algerian rebels were led by the National Liberation Front (F.L.N.) and the Algerian National Movement (M.N.A.). In 1962, the war was over in North Africa. The bloody fight for independence had started with a general strike on January 28 1957. The cease-fire on March 19 1962, was negotiated by General Charles de Gaulle, the President of the French Republic (against the resistance of the French General Jacques Massu and his paratroops in Algeria). The first election for independent Algeria was on July 1 1962, and Ahmed Ben Bella became the first president. Thus it came about, in September 1962, that I, a future paediatrician from Erlangen, Germany, joined the Service Civil International as a volunteer doctor and found myself in a battered French fort near the Berber village of El Khemis, in the barren Tell-Atlas mountains in Western Algeria near the border with Morocco.

What did you take from that experience?

The conditions were primitive in this chantier de l’amitié where other European volunteers helped repair, or build new houses for Algerian refugees.

The days were hot, the nights cold, with rain often dripping through the shattered roof. We slept on the ground. And every night we each had to inspect our mattress to be sure that no scorpions were hiding under there, or worse in the sleeping bag. Sometimes there was still shooting going on at night. We were protected by the F.L.N. I was the only doctor in a large rural area with ten villages where I was responsible for organizing out-patient clinics. The Algerian refugees, regrouped because of military conditions, also lived in camps of tents or gourbis , huts made of grass, branches and tent squares.

Many patients, about 100 a day, mostly women and children suffering from respiratory and intestinal infections, malnutrition , trachoma , skin diseases, and, of course, tuberculosis, came to our daily clinique in the fort, where an English nurse and a Swiss girl assisted me. I was successful in extracting several rotten teeth from the mouths of the two wives of the village chief nearby (fortunately, I had brought dental instruments with me from Germany), thus my reputation as El Tabeeb (The Doctor) was firmly established, and I was often called out, even at night.

What do you still carry with you?

In the following 36 years as a paediatrician and oncologist I saw many infants and children die, but I also saw many who survived, even from terrible diseases like leukemia and cancer. This was due to modern medicine, new drugs, well-equipped hospitals. However, no recovery from imminent death to life, and solely through my own hands, remains more vivid in my memory than this poor little baby outside a shabby Berber tent somewhere in North Africa.