by Paul Lafon , 2 September 1962. (Text translated by David Plamer and Greg Wilkinson)

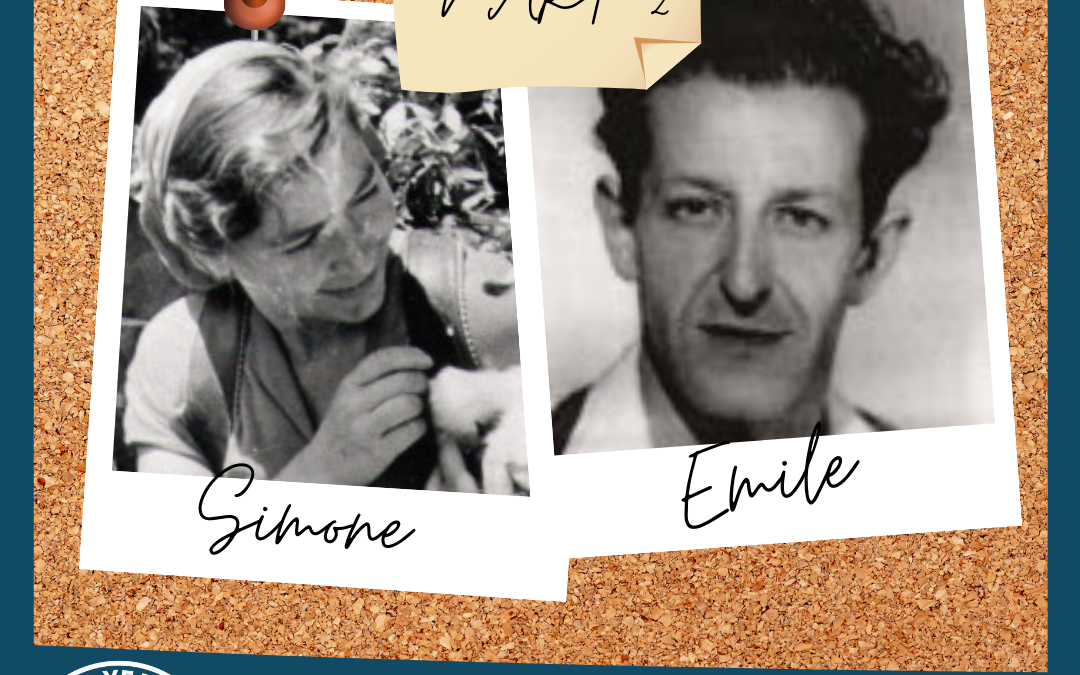

Caught between an unhelpful French administration, and growing racial hostility in the country, this task was also to prove impossible. While trying to maintain an S.C.I. presence, Emil and Simone had the idea of setting up on their own, far out in the countryside near Bouzarea in the western suburbs of Algiers.

The people in that area were Kabyles who had migrated to the Algiers suburbs in search of work in the city. and, built themselves shacks in a shantytown well away from the centre. Emil and Simone settled in the area, she teaching and doing social work, he taking up woodwork, the trade he had learned at home in Switzerland. He combined that with upholstry and leather- work with a view to a rôle in vocational training for young Algerians faced with unemployment or poverty wages. They rented a small property, almost in ruins but, beautifully situated on a steep hillside overlooking the sea. They aimed to live simply, experimenting with poultry and rabbit farming, and sharing the benefits of the experience with their neighbours.

They were confronted with great difficulties due to the state of war in the country. Their project had no official authorization and they feared that the unfriendly administration might shut it down ; so teaching had to be done clandestinely. In the later years of the independence war, official policy changed to allow schooling for all children, so Simone taught children who had been rejected by the l’Ecole Communale in Bouzarea.

Emil had more difficulties with his project. He was a foreigner, and he didn’t have a car or telephone to reach the paying customers he would need to make it viable. He had to fall back on poultry and rabbits, and selling what that produced. Simone worked part-time as a secretary, but had to travel a long way to and from work.

In July 1956 they set up a small work-camp. Emil was promptly arrested, right in front of their house. Simone stood by helplessly as the gendarmes handcuffed him and marched him away. Emil was kept in custody and interrogated for several days and was then to be expelled from Algeria. On what pretext, no one knew. . Probably enough that he was Swiss, an alien and Secretary of the Algerian branch of S.C.I. ? A British S.C.I volunteer who had arrived in the country the day before, found himself expelled along with Emil.

Undaunted, Simone carried on alone while friends took steps to get the expulsion order reversed. Two months later they were told that the order had been cancelled, but no-one was ready to give Emil the formal authorization he needed until he managed to get through to the French government Prefet of Marseille. Back in Algeria he was still harassed and threatened with arrest, until well-connected friends helped secure him the temporary work permit he needed to stay.

All through the War of Independence, Emil and Simone – who could have led a comfortable existence in Switzerland – carried on where they were, in a country torn apart by colonial war and racial hatred. Soon after his return, Emil had to come to the aid of former S.C.I volunteers who had been jailed for some humanitarian gesture that was officially taken as giving support to the enemy. Simone too would try to bring help to former volunteers or their families (French or Algerian), volunteers guilty of ‘fraternization’ in work-camps on Metropolitan French or Algerian soil.

As years and horrors went on, Emil and Simone were still holding out, and even consolidating their activities. With help from their friends they were now epuiped with an old car and phone, so Emil was finding more work than he could manage. He had plans to develop his craft courses and construct a building workshop after having built a wooden schoolhouse. Meanwhile racist violence claimed more and more innocent victims on both sides. Liberal- minded Europeans could be killed by Algerian nationalists, as could Algerians who collaborated with the French authorities. [French forces and paramilitaries were often a law unto themselves in dealing with Algerian rebels and suspected sympathizers. Translator’s note] A climate of fear and insecurity prevailed in the country.

Then, after the signing of the Evian Accords and the cease-fire on 18 March 1962, came the most horrible period of all. Faced with a seemingly unbeatable Algerian (F.L.N.) independence movement, the French O.A.S [Secret Army Organisation. Translator’s note] unleashed its own terror campaign. Any Algerians who dared going to work risked sudden death, and any Europeans suspected of opposing the O.A.S could also pay with their lives.

Emil and Simone stayed on. Three weeks before the cessation of the O.A.S terror campaign, Emil and Simone disappeared from their home. They were said to have been abducted and killed by ‘last minute militants’ eager to prove themselves before it was too late. The victims’ bodies were never found.

This is a great irony, when we think of how much good these two remarkable people had done with and for the Algerian people. Materially and morally. I can’t say how much I admire the way they lived their lives and their way of thinking. I would simply like their lives and actions to be better known, to future generations who will also have many problems to solve.

P.L.

According to Algerian sources, an Algerian who commited the crime was later executed by the F.L.N. as a collaborator, a ‘last minute militant’ who hoped to redeem himself by killing Europeans. See also file number 11203.12 on Simone Chaumet & Emil Tanner. S.C.I.International Archives.