by Paul Lafon , 2 September 1962. (Text translated by David Plamer and Greg Wilkinson)

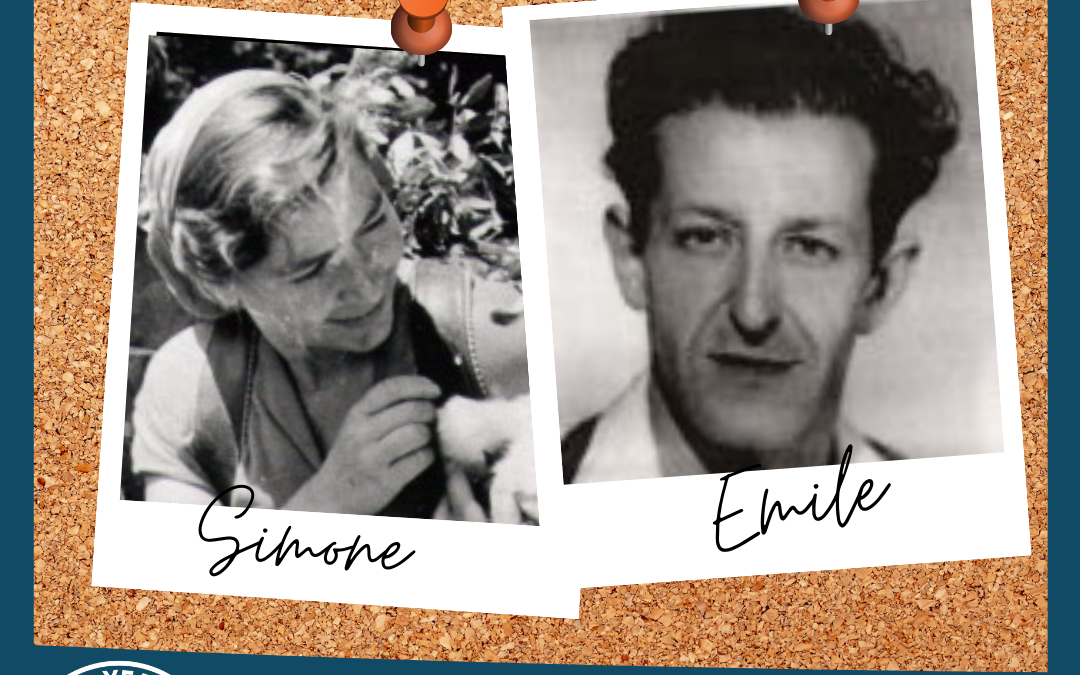

Some three months ago – more exactly on the 25th May 1962 – our very good friends, Emil and Simone, were torn away from an admirable task and an exemplary existence . . . They were brutally dragged away from their home at gunpoint by people so lost in their own miseries that life no longer had any meaning for them. Emil and Simone have not been seen again. Everything leads us to believe that they are no longer of this world . . .

So unthinkable, that up until now, I have been unable to bring myself to express all the fondness we felt towards them; we couldn’t believe the irreparable had really happened . Nevertheless we must, as of now, try and say what they lived for, why they faced danger in the way they did. So, here I will try and set a frame into which I and others can relate what we recall about Emil and Simone.

First of all, Simone Chaumet, who I first got to know in around 1951, when she replied to a call from S.C.I. to fill a vacancy – a difficult job in a workcamp in Kabylie. It was a tough life for those volunteers, and there were some psychological problems. Well-balanced and intelligent, Simone helped raise the morale of the team. ( I wonder where she came from . . .) Born during World War 1, she had never known her father who had been killed in action during the great slaughter. Her younger years were marked by this trauma, and that may have contributed to her great sensitivity. Her mother got married again, and Simone became very fond of her new father. He was an adventurous man, eager to travel the world, and took his wife and their two girls, to Algeria and Haiti in the Caribbean. On returning to France they settled in Cannes. Simone was drawn to her father’s generous nature, and it was a great loss to her when he died, still young.

To begin with, I believe, she went to Paris and worked with backward and maladjusted children – the toughest of jobs, which she very much enjoyed, never losing confidence in life. During WW ll , working in a youth hostel in the Basses Alpes, Simone and a friend Jeannine took to hiding a group of young Jews. For months, then years they hid them in their youth hostel , ‘ l’Auberge du Fanget ‘ , 1500 metres up a mountain.

In memory of Simone, I called by there this summer . The youth hostel has become a hotel, but an old shepherd nearby still kept alive the story of Simone, Jeannine and the Jewish children who were saved by their devotion and resourcefulness.

However, there were still other tasks to be undertaken, and, for Simone, it turned out to be the challenging task of rehabilitating young people deeply damaged by their experience in German concentration camps. Sadly, on one occasion, she was unable to prevent some of the young boys killing some German prisoners. That also left its mark on her. She needed to find some other sort of work.That is what brought her to Service Civil International, a cause to which she devoted herself with characteristic relentless enthusiasm. She took part in workcamps in Europe and England, then followed more in Algeria where she came into her own.

At that time S.C.I Algeria realized that providing basic education was the most useful contribution it could make in troubled times. Simone took naturally to the spirit of ‘fraternization‘ (solidarity with the other) and decided to settle down in Tikiouache, a remote village in Kabylie. There, she intended to show what friendship could do for mankind, sharing the plain and simple life of the Kabyle. She lived in a hut made of mud and branches. She didn’t know the local language but set to work teaching people to read and write (in French, which might then make their lives easier in Algerie Francaise). The French-teaching led into other basic skills and might seem useful to a deprived population. People were keen and that led to the opening of a village school … From education, to health and social welfare, postal procedures and administrative difficulties, in long discussions with people who already knew some French.

Over several years, first in Tikiouache then in Ighil Khellil, Simone lived with meagre financial support from friends (including Albert Camus, now and then ) . Her life might have seemed saintly, but not on any doctrinal lines. She may not have been an atheist, but had not had a religious upbringing and told people she was unsure whether God existed or not. She was guided by common humanity, the ideal of service to mankind. For her, there could be no sitting on the fence in human relations, and she knew how to act on generous feelings, and avoid some of the traps that may arise.

But hardship took its toll, and Simone needed the support of like-minded friends, like the people she knew in the S.C.I. This led to another demanding project, teaching in the most deprived of shanty towns around Algiers , Boubsila ( Berardi) – a tough experience. There she was not dealing with simple Kabyle villagers eager to learn, but with a rough and ready mix of outcasts. Some were hostile, jeering, only a few of them were really interested in school. But that could still make it worthwhile, for all the obstacles and distractions in her way.

Nevertheless, this proved too much, and again she turned to old friends, and started work in the S.C.I. office in Algiers, until Emil Tanner arrived from Zurich to take up the position of Algerian Branch Secretary. He had already done a good job as Workcamp Leader in Southern Italy, an upright hardworking idealist. A frugal man himself, Emil was deeply concerned with the conditions he found in Algeria, and soon came to admire the woman who would become his supporter and companion . . .

Together they organized S.C.I workcamps. Soon they were called to help set up a major relief project following the Orléanville earthquake in 1954. That entailed the reception and co-ordination of many untried volunteers with little grasp of the work to be done or the complexities of life in Algeria. Apart from the challenge of creating an effective workforce, the independence war was brewing. ‘The Uprising‘ broke out on 1st November 1954. That meant more difficulties. The S.C.I. had to close down their big Orléanville workcamp and concentrate on smaller ones.