But my time was earlier, in 1955 – or was it the following year? – when the work was only half done. The trouble is I remember some times and places quite clearly, but cant put dates to them or even be sure what order they came in. I remember camps in Britain, Germany and Algeria but not how I got from one to the next or what happened in between. When I began writing, I tried to piece the bits together and work out the most likely order. I used my common sense, remembering sun in one place, frost in another. Mannheim was definitely in the winter, but which winter? Probably the second, I decided, since I must have been sent to short camps in Britain before a long one abroad. On trial, as it were. Then I found a list of SCI work-camps on the internet. The UK camps I remembered came after, not before, the Mannheim camp in Germany, and that was in January 1955. Later there were two other camps, in Worms and Bruhl, but the second I could not get a proper fix on.

Dates don’t matter, experience speaks for itself, the narrative in a time of its own? Yes, but when we try to make sense of real events, it helps to know what order they came in, unless we can also dispense with cause and effect. Memories may also be compared to observations in a scientific experiment. To be reliable, an experiment must be repeatable, observable by different people in different places. History is never repeatable in that way, but it is more reliable if several witnesses agree: their versions will never quite repeat, if we are to believe them, but must at least correspond. Either way, there’s a sort of democratic truth in both science and history…

Since starting to write about Algeria, I’ve come across a snapshot of the team on my first camp. It includes a woman I thought I remembered from another camp, in Lebanon, a year and a thousand miles away. Now I’ve heard from a man I worked with at a later camp in Algeria. Unlike me, he kept diaries. For that period at least I can check my memories against his notes made at the time. So far, I’ve not been proved quite wrong, but reminded of things I’d quite forgotten.

When I started writing on Mannheim, I did get it wrong. I moved the camp from one winter to the next, and that led to several false inferences. For instance, if I didn’t drink on my first camp in Algeria, this might have been because I had not yet been corrupted by crates of Karneval hock in Germany. If, as now seems likely, the Karneval booze-up came first, then it may have been that experience which put me off drinking in a country awash with strong red wine. Rather surprisingly the little yellow songbook of Service Civil International included the old drinking song, Chevaliers de la Table Ronde. ‘Et la tete sous le robinet!’

If common sense can play havoc with memory, how reliable is it for prediction? This morning, Fred (whose allotment we share in Swansea) rang up and asked if I thought Israel and/or the US would attack Iran. Oil sanctions were being tightened and warships exercising in the straights of Hormuz, but I said I thought both sides had too much to lose. Fred, like me, seemed unconvinced. What if some in Israel might welcome havoc on the ground, as would surely result from an air strike on Iranian nuclear centres? Might that not provide Israeli hardliners with a pretext and cover for ethnic cleansing: the removal of Palestinians who stand in the way of a Jewish democracy in Judea and Samaria?

I’m writing this in Wales, January 2012, about Germany in January 1955. That was ten years after the Second World War. And now I have the SCI archive, listing camps in order, country by country and year by year. In January 1955, a workcamp opened at the Eherlenhof youth centre in Mannheim. Over Christmas the following year there was another on a self-build housing project near Worms.

The workcamp in Mannheim

Schritt, schritt, wechsel, schritt – Step, step, change, and step – we could hear the dance teacher’s voice and the quickstep record through a window overhead. The Ehrlenhof, a former Hitler youth centre, was a modern greyish building, now a multi-purpose community centre and we were billeted in one wing, with metal beds in improvised dormitories and a big table to eat off. The centre was set among drab estates, part residential, part industrial, part wasteland, between Mannheim and Ludwigshaven. We were to help turn former bombsites into a miniature wilderness, not an adventure playground in the modern sense, more a miniature…Bavaria perhaps, with hill and wood and stream in close proximity.

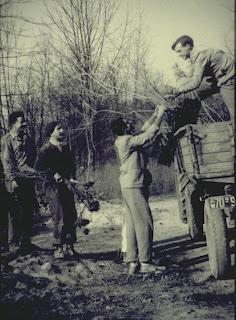

What we found when we got there was still half-battlefield, bulldozed into steep mounds and hollows. This adventure playground was the vision of Herr Hafflinger, who believed that every city child should have a wilderness in reach. Our job was to spread topsoil over mud and rubble, build stone retaining walls, make paths and bridges, plant trees.

Weather permitting, and we were soon less concerned with a green future than keeping warm in the present, the next smoke-break, and the next meal. From the stadtkuche we got a basic diet of potato, cabbage, sausage, and grey bread. In England, there may have still been rationing, but Germany had more to recover from.

Perhaps it was the greyness and austerity of our surroundings or the monotony of manual work, that hardened our hearts and narrowed our minds. Privation doesn’t mostly make people nice. The core of our team was a small group of ‘long-term volunteers.’ We may have been ‘conscientious’ objectors, but now we took the line of least resistance, objecting to anything that disrupted our minimal comforts and routines. We were not lazy, cruel, or anti-German, but nor were we tolerant or welcoming to the idealists and enthusiasts who dropped in to help save the world. We did the job, they talked the talk, we sneered. For a time, if I remember right, we had a middle-aged German ‘head-sister’ called Atta Gruhl. She set store by traditions and rituals, if not grace before meals, then at least a song from the little yellow book. And she served as a lightning conductor for our, mainly English, derision. The English s-o-h can be quite soul-destroying, not least to those it excludes. In contrast, the young German woman who taught dancing at the youth club won our respect. From these poor and war-scarred backstreets, she got a crowd of youngsters, some younger, some older than me, to take each other by the hand and learn new moves. Beyond calling out the steps, this teacher/youth worker rarely raised her voice. She spoke some English and welcomed us to join in, but didn’t make a meal of it. She reminded me of my English teacher Miss Watts, determined and vulnerable, somehow able to create a bubble of commitment and self-belief among unbelievers.

There was nothing solemn about the dance nights. The music was a mix of German pop and the American hits diffused by AFN, the American Forces network. Mannheim was in the American sector, and here, as in Britain – where the conquest took a different form – the GIs were at once resented and admired. Overpaid, oversexed, and over there. I was happier with Sixteen Tons and Hoagy Carmichael than the Yellow Rose of Texas but soon had a regular dancing partner. We seemed to fancy each other and I wondered what to make of it when she saw Bob watching us. Bob was one of my workmates and for no apparent reason, she said she hated him. Bob was no dancer though he had been a lifeguard on the Serpentine. One dance night, my dancing girl did not appear. The next morning Bob told us he’d been out with her.

Bob was a Londoner and looked like a bantamweight boxer, cleft chin and quiff of fair wavy hair. He was a capable worker and handyman and this volunteering was a way of seeing the world. James was a Scot, a former office worker who wore the remains of his suits for the playground work. Our fourth musketeer was Mehdi, a Pakistani Parsee with the air of an absent-minded scholar. His eyes were like the wrap-round ones of Mogul paintings which remain visible in profile. Mehdi told fortunes from palms and collected old railway timetables, which he used to plot imaginary journeys between stations chosen at random. The four of us mostly worked together.

Another workmate, though not part of our little gang, was a Dutchman, Franz. He was good-looking, good-natured, and hard-working with enough humour and presence to hold his own among cynics. Franz spoke several languages and kept on good terms with everyone. At one camp-meeting, people grumbled about the state of the toilets and argued about whose job it was to clean them. The next morning, when we got up for breakfast, the toilets were sparkling. Nobody admitted responsibility but suspicion fell on Franz, clean-cut and well-washed as always.

Almost part of the team, rather more than less in our esteem, was a young Mannheim woman called Helga. She may have been a student but also had a job in town. Sometimes she came in before work to make our breakfast and returned in the evening to help with tea. She was thickset and strong with short dark hair and a plain face redeemed by fine clear eyes. From time to time she also worked with us on site. One day she offered to take us out. We hardly recognised her when she came to collect us. Not dumpy in working clothes but a diva in a long dress, make-up, and fur coat. She took us to a club, or music bar, and bought most of the drinks. None of us had any money. Afterwards, with no late buses, she took us to her bed-sit, where half a dozen of us shared her bed. The best fit, we found, was side by side, neither lengthwise nor crosswise but on the diagonal, corner-to-corner, tallest in the middle. Our work-leader was a Hungarian called Yoshka. He was a mason by trade but with a range of building experience, grasp of plans, and willingness to improvise. He shouted, joked, and cajoled in various languages. Sometimes we pretended not to understand. When he despaired of us, he did the job himself. When it got very cold, we hid behind a bank and lit a fire. We might wheel a barrow over a fire and take turns to lie in it. Yoshka liked puns and crossing languages. From ‘Macht nix’ to ‘Doesn’t matter’ to ‘Thousand meters’ to ‘Kilometer’. He could play tunes on his teeth, making odd faces and tapping out the notes with his fingernails. We once watched him do a sort of rope-trick. At the first stage in the building of a suspension bridge, he threw a rope across a ravine. Rather than wait for one of us to catch it on the other side, he lassoed a tree then climbed across himself.

‘Jesus!’ said James. ‘Fill it with water, and he’d walk across.’ Mehdi once read James’ palm. Usually, he would tell us things about ourselves, more or less credible, but this time he dropped the palm as if in shock. What he’d seen he would not say. James seemed less perturbed than some of us, whether because he was less suspicious or already knew.

I don’t know what became of James, but Bob and my one-time dancing partner went to live together in London. Mehdi later visited my family near Wokingham. His eyes lit up when he spotted a tin of curry powder in our kitchen. He asked my mother for a taste, took a teaspoonful, and swallowed it – the powder, not the spoon.